The political landscape of the Middle East has transitioned significantly since the 19th century, evolving from the Ottoman Caliphate to 20th-century ethnic nationalisms, and later to a resurgence of religious-political identity. Asef Bayat argues that the region is moving beyond the binary of “secular vs. religious,” leading to a ‘grey zone’ where Islamism and secularism intertwine. Modern Middle Eastern states are adopting hybrid models that blend hyper-nationalism with traditionalist rhetoric, focusing on regime stability and economic survival rather than grand ideological visions like Pan-Arab unity.

The article traces this evolution back to the 19th century, during which the Ottoman Empire initiated reforms (Tanzimat) to counter European colonial threats and foster a sense of Ottoman identity. Intellectual movements such as Islamic Modernism, led by thinkers like Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, emerged, advocating for a compatible relationship between Islam and modernity. By the 20th century, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of secular nationalist models like Kemalism and Pan-Arabism defined the era, with significant ideological struggles, particularly between secularists and Islamists.

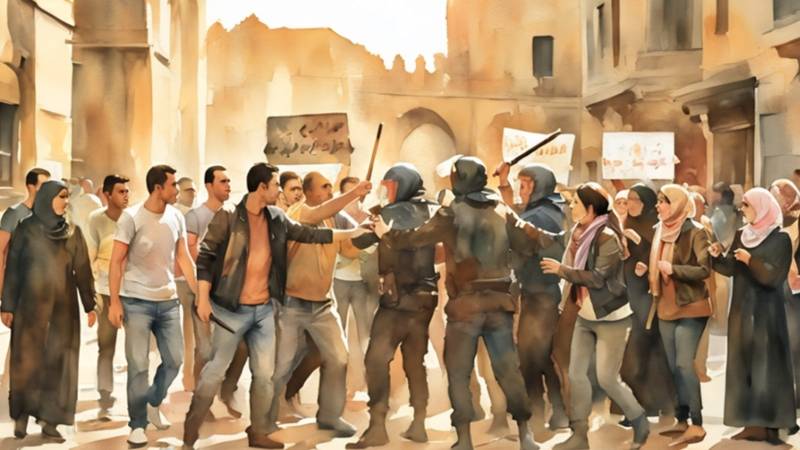

The secular nationalist regimes often failed, leading to a resurgence of Islamism as states like Egypt and Syria became increasingly authoritarian, suppressing opposition through force. This inability to deliver on modernization or military strength, exemplified by the 1967 Six-Day War, allowed Islamist movements, such as the Muslim Brotherhood, to gain support by providing societal needs unmet by secular governments.

In the 21st century, a new dynamic has emerged. The catastrophic impact of the 2003 Iraq invasion led to further fragmentation, while the Arab Spring represented a short-lived hope for liberal reforms. Yet, authoritarianism has generally returned, with states prioritizing security over political freedoms. Gulf monarchies like Saudi Arabia and the UAE are pivoting toward nationalist-developmentalism, embracing high-tech modernity while sidelining traditional religious legitimacy.

Contrastingly, Iran exemplifies the ideological grey zone, maintaining a theocratic framework but facing a society increasingly leaning toward post-Islamism. The state’s attempts at ideological export and regional influence meet domestic pressures for human rights and economic improvement, creating a tension that complicates its future.

Overall, the Middle East is characterized by a fragmented search for identity amidst state fragility, socio-economic challenges, and shifting ideological landscapes, leading to a complex and dynamic political reality that defies traditional categorizations.