The article highlights the historical significance of the New Woodcut Movement in China during the anti-imperialist struggle against Japanese occupation from 1931 to 1945. It begins with the transformative experience of Lu Xun, a Chinese intellectual, whose shift from medicine to literature was influenced by witnessing the apathy of Chinese onlookers during a brutal event in the Russo-Japanese War. Recognizing the need for a national awakening, Lu Xun saw literature as a vital tool for social change.

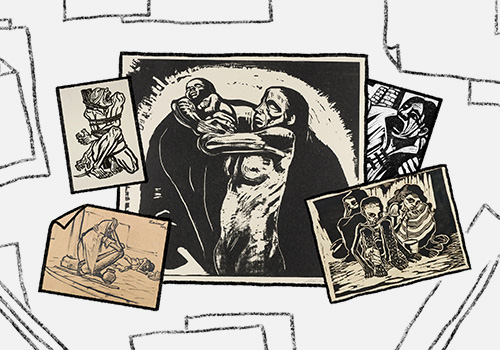

As the Second World War drew to a close, over 24 million Chinese lives were lost, and a generation of artists harnessed the woodcut medium to promote mass education and political agitation amidst conflict. Lu Xun championed this New Woodcut Movement, emphasizing the importance of accessible artistic forms to engage the largely illiterate population. He organized workshops that connected Chinese artists with international influences, fostering a new visual language of resistance.

The article discusses how the movement evolved from Shanghai’s avant-garde circles to the Communist Party’s cultural efforts in Yan’an, reflecting a shift from critiquing suffering to celebrating peasant resilience and collective action. It connects the New Woodcut Movement to broader global artistic responses to fascism and colonialism, highlighting parallels in Mexico and India, where artists similarly used accessible media for political expression.

In conclusion, the article honors the legacy of these artists, emphasizing their role in shaping a visual language of solidarity and resistance against oppression, while advocating for the remembrance of their revolutionary contributions. As Lu Xun noted, art serves as an essential tool in the struggle against autocracy and totalitarianism, preserving historical memory for future generations.