In 2007, Eric Hobsbawm described the Spanish Civil War as a “war of intellectuals, poets, writers and artists” who rallied to the anti-fascist cause, only to feel abandoned by the European workers and peasants who did not heed the left’s appeal. While the American volunteers in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion included many creatives, such as Brooklyn College professor David McKelvy White, most were workers—seamen, longshoremen, and mechanics—rather than the more famous intellectuals who actively documented their experiences.

These volunteers came from a diverse range of more than seventy nationalities, primarily children of immigrants from oppressed backgrounds, such as Jews, Italians, and Slavs, who sought better lives in the U.S. The socio-economic hardships of the Great Depression made many resonate with the progressive reforms of the Spanish Second Republic, which included land redistribution. Their shared values—liberty, equality, and fraternity—formed a bond among the disparate volunteers.

The American volunteers viewed fascists like Hitler and Mussolini as embodiments of feudalism, racial hatred, and oppressive regimes counter to Enlightenment ideals. Many believed they were part of a progressive movement combating reactionary forces determined to enslave them. American universities, particularly in New York, saw active student involvement; notably, City College had a high proportion of Jewish students actively protesting fascism.

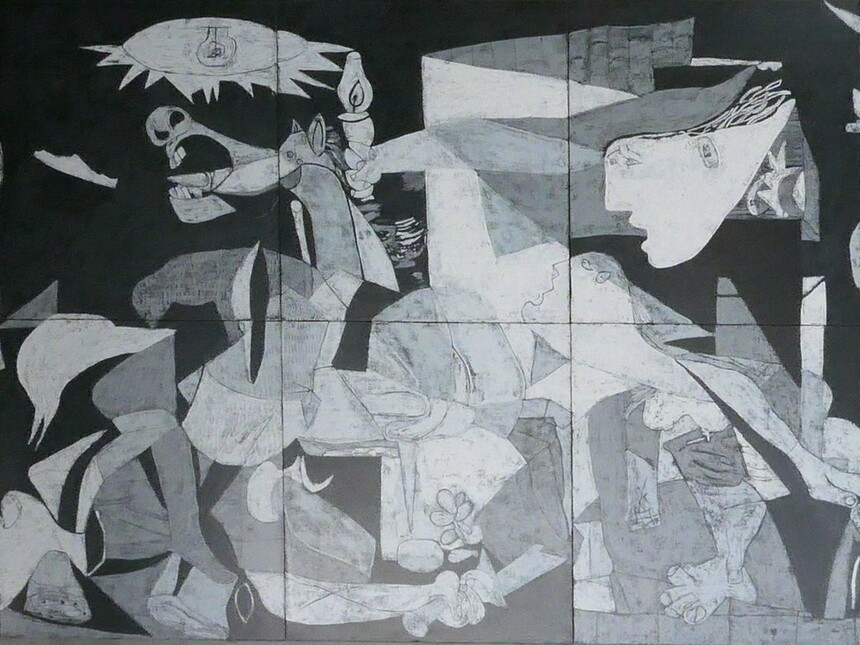

Scholars, artists, and students regarded fighting in Spain as an extension of their education. Many sought to combat fascism not only through direct involvement but also via artistic expression. Anti-fascist art flourished during the Great Depression, with exhibits in New York and creative works addressing the Spanish conflict. American artists often mobilized funds for the Spanish Republic or produced works critiquing fascism, such as Pablo Picasso’s iconic “Guernica.”

Artists and volunteers displayed a commitment to partnership with the oppressed, rejecting the individualistic approach that characterized their predecessors. Some continued to create cultural works that resonated with Americans back home. By the war’s end in 1939, many had sacrificed their lives, underscoring the ideological fervor of the 1930s, where artists believed a flourishing democracy was essential for creativity.

American volunteers recognized the urgent need to combat fascism or face dire consequences for humanity. Their experiences in Spain foresaw the rise of World War II, prompting many to join the fight against fascism when the United States ultimately entered the conflict in 1941.